La 7ma arte… (Italian Cinema)

#littleitaly

If you want to be Italian, you absolutely need to know all about the Italian “7 Arte” (Cinema). Only a few cultural & artistic trends have been as revolutionary as Italian Neorealism (from the end of the second world war to beginning of ’50s) . Just a few notes: Italy was in ruins, the country was still occupied by the Allies, fratricidal guerrilla warfare had embroiled both Fascist loyalists and partisans of the Resistance: the comedies set in upper middle class surroundings that were in vogue at the time, were no longer representative of the country.

You know me, I am literally in love with my country and Italian movies tradition and this time I really hope to help you readers and followers in knowing a little bit more about such an incredible trend. I have selected 10 movies that are symbolic of Italian Neorealism from the period up until 1950, the earliest and most revolutionary years of this cultural trend, with all due respect to the many works that came after (Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers and Pietro Germi’s The Railroad Man, for example, and several works by Fellini). This is our essential Neorealist filmography.

Ossessione – Luchino Visconti, 1943

The movie, breaking the tradition, is also the first film for which the terms Neorealist was used by film editor Mario Serandrei to describe it after watching the filming. Luchino Visconti was inspired by James M. Cain’s novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice (but could not cite it explicitly because of copyrights issues) and told the story of a tramp (Massimo Girotti) who enters into a murky love affair with the wife of a restaurant owner (Clara Calamai) beside the river Po, between Ferrara and Ancona. Breaking decisively with the traditional aesthetics of cinema and the middle-class ethics professed by Fascism, Obsession brings a genuine, raw sensuality to the screen for the first time, which is light years away from the fake smiles and ostentatious wealth of the past. The Republic of Salo destroyed the film but Visconti kept a negative of it until the end of the war. Although it uses professional actors, distancing itself from the dictates of Neorealism that were subsequently established, Obsession was the film that created for the first time on screen a very different ambiance from anything seen before. THE REALITY.

Roma Citta Aperta, Roberto Rossellini, 1945

Perhaps the most famous and emblematic film of the Italian Neorealist era, and the one that for Otto Preminger divided the history of cinema into two parts: before Rome Open City, and after. A film that grew, as many films did, out of the desire to tell a true story, that of Don Morosini, the priest who was shot by the Nazis, and Teresa Gullaca who was killed as she was trying to speak to her husband; the film also becomes a collective account by the Resistance of a city not yet liberated by the Allies.. Filmed in some random studio since Cinecittà was unavailable, and with essential contributions from two well-known actors, Anna Magnani and Aldo Fabrizi, Rome Open City still has an imposing power that astounds spectators. Magnani’s chase scene is still one of the most memorable scenes in the history of world cinema.

Paisà, Roberto Rossellini, 1946 The second in a trilogy of antifascist films by Rossellini, Paisan tells the story through 6 atmospheric episodes of how the Allies advanced through 6 Italian cities from the South to the North. Sergio Amidei and Fellini collaborate again on the screenplay and once again, even more so than in Rome Open City, the collective narrative by a population supplants individual narrative and the ascent from Sicily to the Gothic Line of the Po; also symbolizes the moral ascent of a nation. The Neapolitan street urchin and the bodies of partisans left by the Germans in the river as a warning leave an indelible image.

Sciuscia, Vittorio De Sica, 1946 In Italian, the title of the film, Sciuscià, is the Neapolitan pronunciation of the English word shoeshine, and refers to postwar practice of shoe-shining. The main characters are two shoeshine boys who work in via Veneto and who purchase a white horse as soon as they can, and ride it to Villa Borghese. The boys find themselves involved in a theft; they end up in reform school and experience scamming, violence and revenge in a story that at the time considered so scandalous that the Ministry wanted to ban it from export. But De Sica abandons his earlier works which were lighter and somewhat comedic, and now tells of the discomfort and abandonment besetting the country, drawing once again on a true story: as unlikely as it seems, De Sica really did know these kids who polished shoes for the Americans to save up for a horse! A touching and instrumental cornerstone of Neorealism, this was the first non-American film to win an honorary award at the Oscars’.

Anno Zero, Roberto Rossellini, 1948 The third film in Rossellini’s trilogy takes place in Berlin, which is also devastated by war and bombings. The young Edmund spends his days wandering among the ruins trying to earn money to support his ailing family. His descent into a hell that does not come to a definitive end when the war finishes is heart breaking, and without wishing to reveal too much, leads him to travel metaphorically through human degradation as well as the degradation caused by the bombings. This is one of the manifestations of Neorealism, beloved by Chaplin, containing all the stylistic features of the movement: non-professional actors, lengthy outdoor filming, and a focus on children and profoundly moralistic. A powerful masterpiece that is still outstanding today. The film dedicated to Rossellini’s son, Romano, who died at the age of nine.

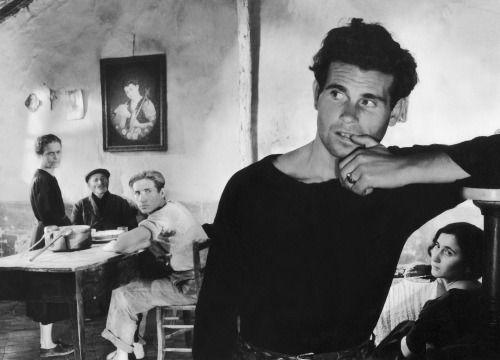

La terra trema Luchino Visconti, 1948

Filmed in the fishing village of Aci Trezza in Sicily, the film was originally intended to be a documentary on their lives, but was later dramatized as a free adaptation of the great realist novel I Malavoglia by Giovanni Verga. Entirely shot in Sicilian dialect and subsequently dubbed to make it more comprehensible, the film tells about the struggle of a family of sailors, in particular ‘Ntoni, against unscrupulous wholesalers. A theme close to Visconti’s heart, that of individual insurrection that comes up against a class-based society and capitalist exploitation, even today the film has powerful imagery and an extraordinary sense of morals.

Ladri di Biciclette, Vittorio De Sica, 1948

After the failure of Shoeshine, De Sica wanted so much to shoot this new film that he produced it himself. Written by Cesare Zavattini and based on the novel by Luigi Bartolini, the film tells the moving story of a father and son who eke out a living in post-war Rome and – in the words of De Sica – attempts to “bring out the drama in everyday situations, the magnificent in the small news.”Preferring to remain faithful to his idea of realism, and inspite of the losses he made with Sciuscià, De Sica refused funding from American film producers who wanted Cary Grant to play the lead role, and instead brought in unknown amateur actors Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola in the roles of father and son, apparently choosing them for the way they walked. The film had a cool reception in Italy but was a triumph in Paris, followed by recognition and several awards including an Oscar, a Golden Globe and a Bafta.

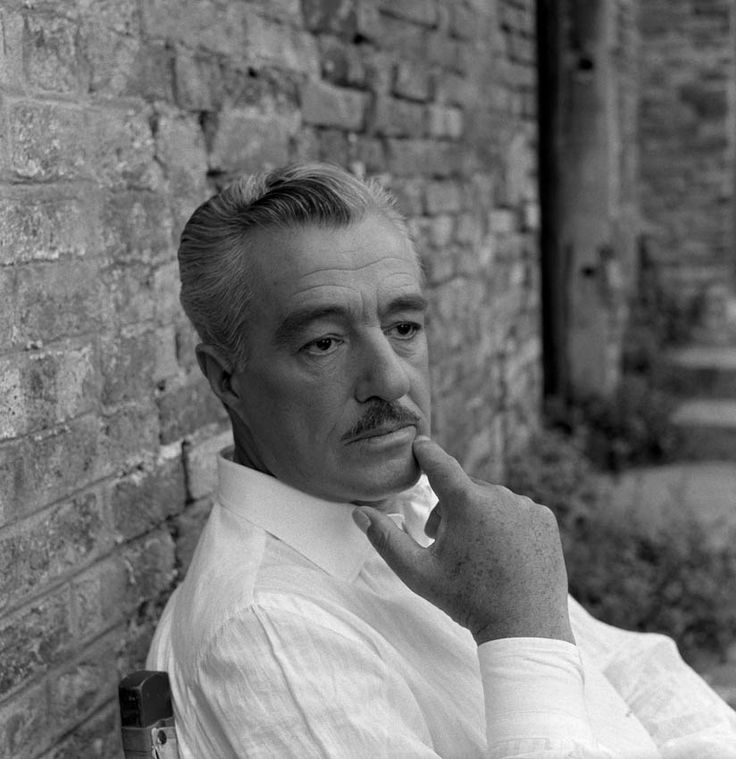

Riso Amaro, Giuseppe De Santis, 1949

The first Neorealist film to have public success in Italy, Bitter Rice, written by Carlo De Santis with Lizzani and Vittorio Puccini, is based on something that happened to the director: in the station in Turin he heard singing and saw it was “mondine” – rice pickers; women who harvested the rice in the paddy fields of Piedmont. He was fascinated, and the story grew out of it of a bandit and his accomplice who infiltrate the rice pickers in the station to escape the police. The film launched the career of Silvana Mangano, selected by De Santis who was looking for an “Italian Rita Hayworth”, for the part. Mangano was rejected at the audition because her clothes and make-up were too flambuoyant, but was reinstated after a chance meeting with the director on the streets of Rome, when he saw her without make-up and with wet hair in the rain. The handsome and tormented bandit is played by Vittorio Gassman.

Stromboli, Roberto Rossellini, 1949

The film tells the story of a Lithuanian refugee who marries Antonio, a released prisoner and sailorman on Stromboli, in order to escape from an internment camp. Massacred in America because of the scandalous Bergman – Rossellini affair the film was shot without a script and with locals in leading roles. Rossellini manages to integrate a profound, almost documentary focus (the tuna fishing, for example, or the evacuation for the eruption) into a sort of autobiographical account, metaphorically telling the story of the pressure he got from the tabloid press over his relationship with Bergman, which was scrutinized relentlessly by the paparazzi and judged by do-gooders and the women of Stromboli alike. The almost mystical and divine nature of the volcano looms over the lives of everyone throughout the film.

Miracolo a Milano, Vittorio De Sica, 1950

Based on the novel Toto il Buono by Cesare Zavattini, the film is a kind of fairy tale starring Totò, an orphan who dreams of living in a world “where good morning really means good morning” and is accompanied by homeless people that he has befriended, becoming almost a mystical leader. The film was originally called “I poveri disturbano” [The poor are troublesome] but the producers feared controversy from politicians. There was much criticism, including that of having betrayed Neorealism and given in to Zavattini ‘s “magical realism”, and even adopting an evangelical tone (it was banned in the Soviet Union). Then again, it was also criticised for being pro-communist. No one liked the idea that the main characters were tramps and they were probably having a good time… The film does in fact deviate partially from the gloomy aspect of the other works included here, probably because of the ending with the spectacular flight of the tramps on broomsticks, the production costs of which almost bankrupted the studio but subsequently inspired the bicycle flight of Spielberg’s ET. But it is also perhaps that it manages to create a link between a difficult situation like the post-war period and a breath of hope that we wanted to include this film as the final one in our top 10; because of its mix of reality and fantasy, which is what cinema is founded on.